- Home

- Dave Navarro

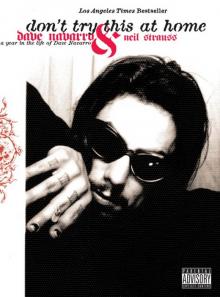

Don't Try This at Home

Don't Try This at Home Read online

Dedication

In memory of

Jen Syme and D’Arcy West

Contents

DEDICATION

june

PART I

THE CONCEPT

PART II

THIS IS HOW I DO IT

PART III

HOW THE RECORD INDUSTRY IS LIKE A UNICORN

PART IV

STALKED

july

PART I

THE FIRST PERSON DAVE’S PAID TO COME OVER TO HIS HOUSE WHO HAS ACTUALLY KEPT HER CLOTHES ON

PART II

LOVE IN L.A: CHRISTMAS FOR GROWN-UPS?

PART III

SHE’S SUCH A GREAT …

PART IV

AN IMAGE

PART V

SPIRITUAL GUIDANCE

august

PART I

THE RHETORIC OF DAVE

PART II

THE GREAT CHILI PEPPERS DEBATE: “BRINGING IT ON YOURSELF”

PART III

THE GREAT STEVE VAI DEBATE: “SPEAK ONLY FOR YOURSELF”

september

PART I

HOW TO GET OFF DRUGS WITHOUT REALLY TRYING

PART II

TEN WAYS TO TIE OFF

PART III

ON DAVE’S DICK

october

PART I

DEAR DIARY

PART II

ABOUT A GIRL

PART III

CRYSTAL KOALAS, PET ROCKS, AND THE TENNIS MOM THEORY

PART IV

THE MYSTERY OF MR. YOUNG

PART V

INVADED AT HOME

PART VI

THE MARCH OF THE BABY UNICORNS

november

PART I

IT’S TOO BAD DAVE CAN ONLY DIE ONCE; HE’S GOT SO MANY IDEAS

PART II

SHOW AND HELL

PART III

CLOSE CALLS

PART IV

GOOD OMENS/BAD OMENS

PART V

IT’S TOO BAD DAVE CAN ONLY DIE ONCE …

december

PART I

THE FIRST TIME (WITH SOUND EFFECTS)

PART II

CUCKOO OR CUCKOLD?

PART III

LOVE IN L.A. II: THE MYTH OF COUNTING ON ONE HAND

PART IV

ONE HOT VISIT

PART V

DEAR DAD

PART VI

PSYCHOBABBLE

PART VII

CLOSER CALLS

january

PART I

THE HEISENBERG UNCERTAINTY PRINCIPLE: A WATCHED OBJECT CHANGES ITS COURSE OF MOTION

february

PART I

NAVARRO HYPOTHESIS #9

PART II

TEMPORARY REPRIEVE FROM DARKNESS

PART III

DEAR ADRIA

PART IV

LOVE IN L.A. III: INTIMACY AND COMMUNICATION

PART V

RUNNING ON EMPTY, SCENE ONE

PART VI

RUNNING ON EMPTY, SCENE TWO

PART VII

RUNNING ON EMPTY, SCENE THREE

march

PART I

TWENTY THOUSAND LEAGUES UNDER THE C: A. JOURUNEY INTO THE MIND OF A GIRL CONSIDERING PROSTITUTION

PART II

CRACKING UP IN THE CITT THAT NEVER SLEEPS

PART III

A SERIES OF ANSWERING MACHINE MESSAGES

april

PART I

THE SWEEP

PART II

THE NOTE

PART III

THE CONFESSION

may

PART I

A NOT-SO-TRIUMPHANT RETURN

PART II

TORI’S STORY

PART III

A TRIUMPHANT RETURN

PART IV

THE OUTPATIENT

june 2000

PART I

“WHAT WAS I THINKING?”

Postscript:

june 2004

PART I

GOOD-BYE TO HOLLYWOOD

PART II

LOVE IN L.A. IV: LOVE DOESN’T HAVE TO CRUSH YOUR HEART LIKE A COKE CAN

PART III

THIS IS HOW WE DID IT

PART IV

TEN REASONS NOT TO TIE OFF

PART V

A FINAL IMAGE

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

COPYRIGHT

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

FOOTNOTES

part I THE CONCEPT

“Do you know what to do when somebody shoots up too much?”

That’s the first question Dave Navarro asked as we began this collaboration on June 1, 1998, making it clear that I had more than a life story on my hands: I had a life. Not a series of past events filtered through the dirty grate of memory, but a heart that was still beating. To document the beating of that heart was the goal, and if the past was relevant at all, it was only as the blood that coursed through that heart and gave it a reason to beat. Or to not beat. Because at times, that heart didn’t want to beat.

That night, Navarro showed me what he called his Spread movie. It began with a phone call to a rehab center. Navarro told the operator that he was in trouble and needed help badly; the operator said she’d call back later. The rest of the movie was a series of scenes he had filmed to the accompaniment of his music. It centered around three images: a spoon in a bowl of Jell-O, symbolizing the nourishment of his past; a spoon with a rock of cocaine, symbolizing the nourishment of his present; and a picture of his mother, the bond that connected both spoons. In the movie, he shoots up with a picture of his mother in the background, an image all the more disturbing if you consider that Navarro’s mother was murdered by an ex-boyfriend, a man Navarro had grown to trust. Occasionally, the camera would pan to a computer screen, which displayed the phone number of his lawyer and directions on how to find a certain song in his CD changer.

The movie seemed disgusting not because of the images, but because of Navarro’s eagerness to exploit a tragedy for the sake of a self-aggrandizing art film. At least, that’s what I thought until Navarro said it wasn’t an art film. It was his will. The song in the CD changer, which he wanted played over and over at his funeral, was “This Is How We Do It” by Montell Jordan.

“That was my checkout movie,” he said. “It was supposed to be a note of explanation before I ended it. I was going to take a bunch of pills afterward, because I thought it wouldn’t be as ugly as being found with a needle in my arm and blood all over the place. I got the idea from Final Exit, which I always considered a how-to manual. But when I started editing the video, somehow it showed me there was something to live for, there was something else I could do creatively. I realized that because I was getting picky about certain scenes and wanted to reshoot parts. I guess I cared.”

Navarro stood up and rolled thick black curtains across his picture window overlooking L.A. (“I bought a house with a picture window so I could imagine myself pissing on L.A.”), as if that would keep the sun from rising. And it did, at least for us and Mary, a statuesque, raven-haired drug dealer who sat mutely on the floor with her arms wrapped around her knees. A beautiful South Dakota girl too smart for her hometown, she moved to Los Angeles seeking a new life and somehow wound up selling drugs to people like Navarro, Leif Garrett, and Marilyn Manson. Sitting limply at her feet was her ladybug backpack and a needle dragon, a felt animal-shaped zipper bag containing syringes instead of the pencils for which it was intended.

All does not seem well at Navarro’s Hollywood Hills home. But at the same time, things have never been better. Since a messy split with the Red Hot Chili Peppers and the suitably named Jane’s Addiction Relapse tour, Navarro has been in a strange transition. In th

e months leading up to June, everything changed for him. His career as a guitarist in two famous rock bands ended; he had a messy parting with the label that was going to release his solo project; he turned his back on the friends and relatives closest to him; he suffered a rough breakup with his girlfriend, Adria; he started shooting up coke and heroin again; and he bought a photo booth.

Socially artistically, and chemically, Navarro restructured his entire life—or had it restructured for him—with the photo booth serving as a way of systematizing the friends, dealers, prostitutes, and strangers passing in and out of it. By the end of this yearlong book project, a process piece chronicling twelve months of his life in photo-booth strips, essays, and conversations, the outcome of these changes will become clear. This is a story that will either have a happy ending or a tragic one: there is no in-between.

“Maybe I’ll die and make the book a bestseller for you,” Navarro said that first night. It would have been easy to laugh off the comment or think of it as a self-pitying plea designed to make the listener feel uncomfortable, but it was not a joke or a test. As he spoke, he tied off his left arm with an RCA cable and plunged a syringe into his arm, tapping the plunger as the phone rang. He picked it up, needle dangling from his skin like a cigarette from someone’s lips, and put the caller, Marilyn Manson’s drug-addled bassist Twiggy Ramirez, on speakerphone. Twiggy had just snorted a fingernail-size line of Ketamine, a cat tranquilizer, and was freaking out. His walls and Star Wars toys were closing in on him, the red wine wasn’t bringing him down, and he wanted to come over.

One of the biggest changes Navarro made in his life this month was in transforming his Hollywood Hills house into a cross between a crack den, an after-hours club, a halfway house, and Andy Warhol’s Factory. It became a fucked-up focal point for wretched freaks and glamorous stars to gather and discover that inside, the freaks feel like stars and the stars like freaks. The house is best summarized by the road sign perched one hundred feet uphill: DEAD END: NO TURNAROUND.

“I used to feel like life was such a fucking chore that all I ever really looked forward to was going home and turning myself off in an environment that was somewhat of a sanctuary” Navarro, shirtless with Calvin Kleins creeping out of his jeans, said about the house’s past. “It had to be immaculately clean and free of responsibility. I was living my life very much in a regimented fashion, following the strict way of health and sanity. I was drug-free and I was so fucking strict about the wrong things, like what I ate and put into my body and how I looked, that I was miserable. I could never leave a dish in a sink because that meant I was focusing on all the outside stuff. There was something to do, and I couldn’t relax as a result of it.”

But when Navarro decided that on an emotional level he didn’t feel any better, he relapsed—returning to the drug habit he thought he had kicked five years earlier. It was a conscious decision, he always says, not a matter of circumstances. At the same time, he started making his checkout movie, and in order to get more footage he opened his house to other people for the first time.

“I decided to give in and just live moment-to-moment how I wanted to, and see if that would do away with the emotional weight that I was carrying. I always felt uncomfortable because I was constantly thinking about what I should be doing and what was coming up. So I decided to say, ‘Fucking hell with it’ I decided to see what it was like to be less uptight. Since the option of death was always available, I had nothing to lose. If somebody came over and spilled a glass of wine on the couch, I could always kill myself.”

Then came the photo booth, a triumph in cynicism, mistrust, and fear of abandonment. Though the project of documenting everyone who steps in the house (minimum one photo strip per person per month) over the course of one year is so many things, at its core it is an experiment to prove or disprove Navarro Hypothesis #1: The only people who stay in your life are the ones you pay. Your friends and family will disappear, but the cleaning lady, the pizza delivery man, and the drug dealer are forever.

So who do we have in June? Eight rock stars, seven television crew members, six music executives, five sycophants who were either kicked out or barred from the house by their visit’s end, four actors, three drug dealers, two prostitutes, one cleaning lady, and a dog.

The photos tell one story; the house tells another. The month had its share of tales that would be whispered about at Hollywood bars: Leif Garrett coming over at 6:30 A.M. to fix a curtain rod in exchange for drugs; Rose McGowan picking up what she thought was a stack of poker chips only to be told by fiancé Marilyn Manson that it was a masturbation sleeve a prostitute had given Navarro; the entire crew of a television show waiting outside for forty-five minutes as the producer futilely tried to wake a partied-out Navarro, checking his pulse to make sure he was alive; Navarro jotting down his phone number on a syringe wrapper for a horrified music executive; and Navarro briefly dating an über-groupie in order to put his hands where Jimmy Page’s hands had been.

Then there’s the night Manson and Dave spent two hours computer-manipulating a photograph of a scantily clad Courtney Love lying sprawled outside Trent Reznor’s hotel room so that they could first transcribe the psychotic rant she had written in lipstick on his door and then blow up a picture of her vagina to use as an album cover for Dave’s demos.

But perhaps the best tales that the month produced took place on the rare nights when Navarro actually left his dwelling place and social laboratory, a feat in itself considering the strong magnetic pull the house has come to have over him. And each time, his destination was a party at the Playboy Mansion (that is, with the exception of a two-minute appearance at his own birthday party at the club Barfly on June 7, which Hugh Hefner actually attended with the three blondes he was concurrently dating in tow).

For the first of two Playboy parties in June, Dave and Twiggy rented a limousine to bring them to the mansion. But as the car arrived to pick them up, Navarro turned to answer the door and knocked one of his small glass unicorns off a shelf. Picking it up, he noticed that its horn had broken off. He searched the floor, but the tiny horn was nowhere to be found. The limo driver honked impatiently.

“Let’s go, let’s go,” Twiggy urged, jumping around with his usual childlike energy.

“Dude, I can’t,” Dave said darkly, crawling around the floor on all fours. “I have to get that horn. I feel like bad things are going to happen to me if I can’t find it.”

Obsessed, Navarro spent the next hour using a lamp with the shade removed as a substitute flashlight, searching for the horn whose loss he considered a symbolic disaster. This logic was either drug-addled obsessive-compulsive behavior, or an excuse to keep from going out. Eventually, he found the unicorn fragment, which had been kicked underneath the rug, and made it to the party, where—with the lucky horn in his pocket—he picked up a Playmate and a Penthouse Pet. The Playmate was an argumentative model who quickly earned herself the nickname The Pooper as she constantly tried to manipulate the events of the night in the direction of gas stations, diners, and bars where she could take foul-smelling shits in private. The drop-dead gorgeous Pet, renamed Where’s My Purse after misplacing her handbag eight times that night, went on to earn herself the honor of being quite possibly the stupidest woman ever to sleep with Twiggy. And that says a lot. In later visits to Dave’s in June, Where’s My Purse would get lost as many as twenty times trying to find the house, calling for new directions with each wrong turn.

Dave’s next visit to the Playboy Mansion would be his last; not by choice but by necessity. His companion this time was Melissa, a petite brunette with a large wound on her back as a result of recent friction with the carpet in Dave’s studio, which still bears the corresponding bloodstain. Melissa had been excited about the party for months, spending three hours that evening getting ready. When she finally showed up at Dave’s, dressed in new clothes from Fred Segal, she found him sleeping. She was so upset that she burst out crying as she shook him awake.

Don't Try This at Home

Don't Try This at Home